Imagine that you’ve been hit by ransomware.

All your data files are scrambled, you’re staring at a ransom note demanding $1000, and you’re thinking, “I wish I hadn’t put off updating that cybersecurity software.”

When the dust has settled – hopefully after you’ve restored from your latest backup rather than by paying the blackmail charge – and you’ve got your anti-virus situation sorted out, your burning question will be…

…where did the malware come from?

But what if, no matter how carefully and deeply you can, you can’t find any trace that there ever was any malware on your computer at all?

Unfortunately, as our friends over at Bleeping Computer recently reported, that can happen, and it’s one case where not being infected yourself is actually a bad sign, rather than a good one.

The Bleeper crew have had several reports of users whose files were scrambled from a distance across the internet, by ransomware running on someone else’s computer.

It’s a bit like suffering from a malware attack while you’ve got a USB disk plugged in – if your computer can access files on the plug-in device over the USB cable, you’ll end up with files scrambled on both your laptop and the USB disk, but the malware program itself will only ever show up on your laptop.

The USB drive will be affected but not infected

The same sort of thing often happens across the local network in ransomware attacks inside a company, where a single infected computer on the network ends up scrambling files on all your servers because the user happened to be logged in with an account that had widespread network access.

In the end, hundreds of users and hundreds of thousands of files many get affected, even though only one user and one computer were ever infected.

Over the internet?

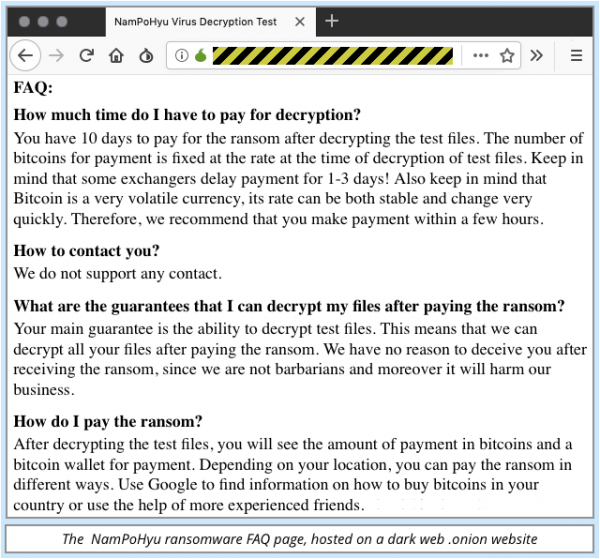

Bleeping Computer has dubbed this latest strain of remote-control ransomware NamPoHyu – that’s the moniker that pops up when you visit the malware’s web page – but the name doesn’t help much, because there isn’t any malware file that you can go looking for if the attack started from afar.

It could have been almost any ransomware that did the damage, and that’s the problem.

Of course, this raises the questions, “How on earth can file-scrambling malware work over the internet, and how can crooks purposely aim it at me?”

Sure, lots of companies, and many home users, run web servers, gaming servers, remote access servers, and so on, but who runs plain old file servers over the internet?

Who would leave their computer sitting online so that crooks anywhere in the world could type in a Windows network mapping command such as the one below?

C:> net use j: 203.0.113.42C$

If your computer is online at the IP number 203.0.113.42 and accepting Windows networking connections, the above command will leave the crooks with a J: drive that lets them wander around your files at will, as easily as if those files were on their C: drive.

Few, if any people, would let crooks share their local drives on purpose, but surprisingly many leave their local disks open by accident.

Microsoft’s file-sharing protocol – the protocol that lets you open up your disks with the command net share and connect to other people’s disks with net use – is now officially known as CIFS, short for Common Internet File System, but it started life with the jargon name of Server Message Block, or SMB.

Back in the early 1990s, when prolific Aussie coder Dr. Andrew Tridgell started his open-source implementation of SMB so that Linux and Windows computers could work together more easily, the acronym SMB was turned into the pronounceable name “Samba”, and that’s the name you’ll probably hear used most frequently these days, by Windows and Linux users alike.

Samba is what does the sharing, and shares are what you connect to on servers that you’re supposed to access.

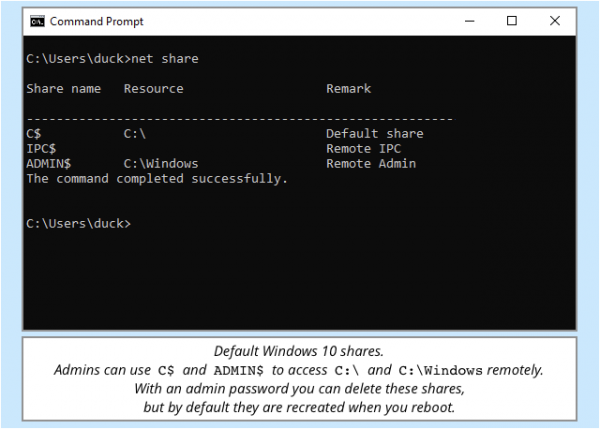

You can create your own shares (use the command net share to list them all) with handy names, such as DOCUMENTS or SOURCECODE, and Windows will automatically add some special ones of its own, notably two default (and hard-to-remove) shares called C$ and ADMIN$ that give remote access directly to your C: drive and your Windows directory respectively.

Annoyingly, shares with names ending in $ are hidden, so it’s easy to forget they’re there – something that many people, sadly, do.

Not just anyone can hack into C$ and ADMIN$, of course – you need network access directly to the target computer, which you wouldn’t normally get through a firewall or home router, and you need an Administrator’s password.

So far, so good…

…except that, as we write about rather too often, many users have sloppy habits when it comes to choosing passwords, making them easy to guess, and many devices that were never supposed to be accessible to the outside world show up by mistake on the internet search engines.

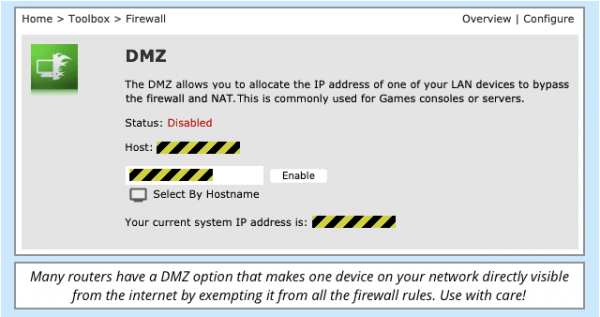

WARNING. It’s tempting, and dangerously easy when you're sitting at home having troubles playing the latest game, to get around your setup hassles by simply lowering your firewall security shields. Maybe you went into your router and temporarily told it that your laptop was your “gaming server”, for example? If you allowed in all traffic for troubleshooting, how many crooks took a peek while your security was off? If everything started working while you were testing, did you remember to put your shields back up afterward, or did your temporary fix become your permanent one?

Remote ransomware attacks

Simply put, if crooks can see your Samba shares from out there on the internet, and can guess your password, they can theoretically wander in and do what they like to your files.

They can therefore attack your computer – manually or automatically – simply by pointing one of their computers, or someone else’s hacked computer, at yours and deliberately “infecting” themselves with any network-enabled ransomware they like.

Many, if not most, modern ransomware samples include a feature to find and attack any drives visible at the time of infection, to maximize damage and boost the chance that you’ll end up having to pay – that includes secondary hard disks, USB devices plugged in at the time, and any open file shares.

In other words, if you’re at risk of a remote ransomware scrambling attack, the real situation is actually much worse than that.

It may sound like cold comfort, but a ransomware attack is one of your “least bad” outcomes because your files get overwritten but not stolen.

Instead of ruining your files, the crooks could choose simply to copy them off your network to use later, and that sort of attack [a] would be much less noticeable [b] would be impossible to reverse, and [c] would affect and expose anyone else whose data was stored in those files.

What to do?

Pick strong passwords. And don’t re-use passwords, ever. You can assume that crooks who find your password in a data dump from a hacked website will immediately try the same password on any other accounts or online services you have. Don’t let the password for your online newspaper subscription give the crooks a free ride into your webmail, your social media, and any computers and file shares you have.

Keep your shields up. If you’re having connection troubles, resist the temptation to “turn off the firewall” or “bypass the router” to see if that solves the problem. That’s a bit like disconnecting your car’s brakes and then going for a ride to see if performance improves.

Run anti-malware software. Even on servers. Especially on servers. Your laptop isn’t supposed to be open to the internet, and generally won’t be. But many of your servers are online and accessible to the world on purpose, so although they can be protected by a firewall, they can’t be fully shielded by it, and that’s by design.

Consider using a ransomware blocker. Tools like Sophos’s own Cryptoguard can detect and block the disk-scrambling part of a ransomware attack. This offers you protection even if the malware file itself, and its running process, is out there on someone else’s computer that you can’t control.

Make regular backups. And keep at least one recent copy offline, so you can access your precious data even if you’re locked out of your own computer, your own network, or your own accounts. By the way, encrypt your backups so that you don’t spend the rest of your life wondering what might show up if any of your backup devices go missing.

Post a Comment